Japanese identity has rarely remained static in the past 150 years since opening up in the Meiji Restoration (明治維新) of 1868. The way in which Japanese see themselves has long been the determinate of whether or not Japan participates as member of the Asian community, the Western world, or neither. This paper will address a brief evolution of Japanese identity and its impact on its relations with its neighbours. It will later address the problems Japan faces as it attempts to become a ‘normal’ country.

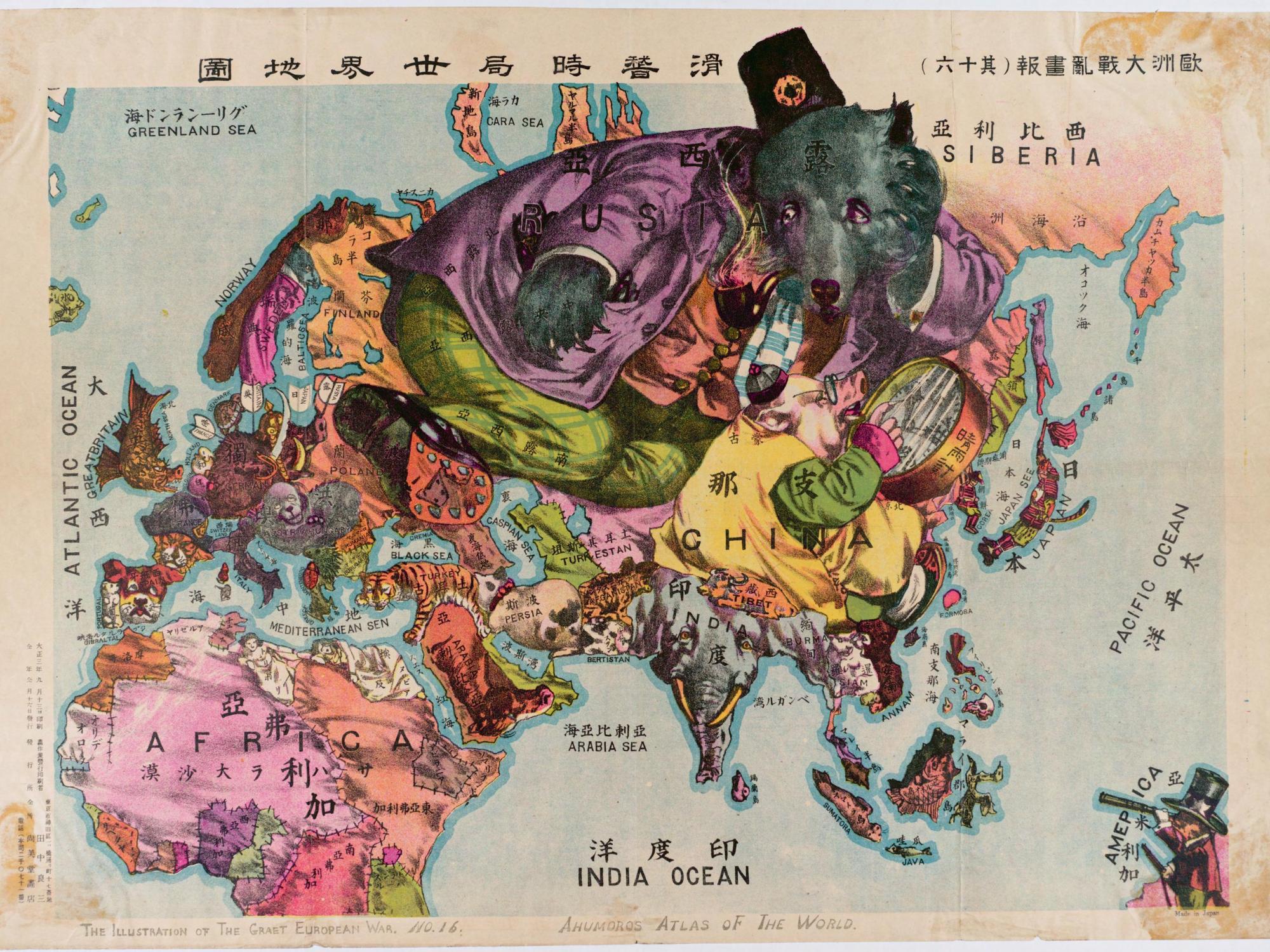

Japan was forced to open to the West in in 1953 with the arrival of Commodore Perry in Yokohama. The Shogunate (幕府) was later deposed in 1968 in a revolution that resulted in the promotion of the emperor—from a largely ceremonial role—to head of state. Japanese fears of colonization had forced Japan to end its closed nation policy (鎖国). During a period of intense industrialization, in which Japan borrowed concepts heavily from the West, Japan also fostered elements of extreme nationalism centred on the emperor’s divinity and the supremacy of Japanese people. The idea of “Nihonjinron”/日本人論 (Rozman, 2012, pg. 32)—literally theory of Japanese people—created a notion that Japanese people were unique. According to Taggart in Japan and the Shackles of the Past, the idea of a “supposedly pure Japanese culture had predated Meiji.” (2014, pg. 76) “Kokugaku”/国学 (Rozman, 2012, pg. 40), the study of Japanese uniqueness flourished between the rise of rangaku/蘭学 (Dutch studies/Western studies) and the decline of kangaku/漢学 (Chinese studies) in the late Edo Period. However, it was not until the opening of Japan, that Japan entirely departed from its Asian identity. The “leave Asia”(Taggart, 2014, pg. 77) argument gained prominence—with the endorsement of influential academics such as Fukuzaka Yukichi (福澤 諭吉)—after Japan’s victory in the Russo-Japanese War (1904-05). Japan eventually returned to Asia in the events leading up to the Pacific War, but as an imperialistic power. It had adopted an anti-Western demeanour and a paternalistic outlook on its East Asian neighbours. After its defeat in the Pacific War, postwar Japan was built upon the foundation of an “economic identity” (Rozman, 2012, pg. 28) through the economic policies of the Yoshida Doctrine, and a “political identity” (2012, pg. 28) that continued to centre on aspects of Japanese uniqueness.

In 1957 Japanese Prime Minister Kishi Nobusuke (岸信介) specified the county’s postwar foreign policy objectives under the ‘three basic principles’. These principles outlined Japanese commitment to “United Nations centrism”(Hosoya, 2012, pg. 172)—complimenting liberal internationalist desires for Japan to be part of an international community, “cooperation with free states” (2012, pg. 172)— specifically referring to Europe, North America and Japan—and “holding fast to being a member of Asia” (2012, pg. 172)—formally rejecting the ‘leave Asia’ camp. It was not until government of Fukuda Takeo (福田赳夫) that Japan clarified its position in regards to Asia. The Fukuda Doctrine—outlined in 1977—stated that Japan would never seek hegemony in Asia and that it saw itself as a peer among equals in the Asian community. Hosoya claims that the Fukuda Doctrine was a success insofar that it allayed anti-Japanese sentiment in Southeast Asia and set forward a new path of relations where Japan was an “equal, rather than paternal,” (2012, pg. 179) state in the region. Japan attempted to create a similar state of affairs with China with the Treaty of Peace and Friendship Between Japan and the People’s Republic of China in 1978, when Japan once again committed to peaceful relations and non-hegemony.

A positive perception of Japan among Southeast Asian nations has endured, but for China, the early 1980’s reached the height of post-war relations and positive perceptions. Protests during Prime Minister Nakasone Yasuhiro’s (中曽根康弘) visit to China shocked many Japanese, leading to an increase in anti-Chinese sentiment—ending a long upswing in perceptions. Various events in the following decade would force Japan to alter its identify once more in respect to its neighbours. Rozman believes that three events had a particularly large impact on Japanese identity in the post-Cold War world. He lists the “Malta U.S-Soviet Summit” (2012, pg. 160), the formation of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) group, and the death of Emperor Hirohito ending the Showa Period (昭和時代). Later, Japan faced another dilemma with the 1991 Asset Price Bubble (バブル景気) eroding the strength of Japan’s ‘economic identity’. In the following decade Koizumi Junichiro (小泉純一郎) formally expired the Yoshida Doctrine.

Japanese politicians sought to redefine Japan in the post-Cold War period by pursuing the creation of a “normal” Japan. Ozawa Ichiro (小沢 一郎), a former LDP heavy weight, coined the term in a 1993 book titled Nihon Kaizō Keikaku (日本改造計画). The term has since been used by a myriad of politicians and academics on both sides of the political spectrum. Despite political differences and approaches, the aim of creating a ‘normal country’ with an independent foreign and security policy has remained universal among advocates of the concept. Hatoyama Yukio’s (鳩山由起夫) attempt to evict U.S Marines from Okinawa and Abe Shinzo’s (安倍晋三) 2014 constitutional reinterpretation symbolize two different approaches to accomplishing the same goal—a normal Japan.

The pursuit of a ‘normal’ Japan in parallel with an unfavourable perception of Japan by South Koreans and the Chinese has led to a “new leave Asia argument.” (Rozman, 2012, pg. 37) Where Japan has been successful at improving its image in Southeast Asia, it has failed woefully at doing the same in East Asia. Koreans and Chinese harbour strong anti-Japanese sentiment as a part of the foundation of their own national identities. Rozman claims that South Korea and China blocked Japanese efforts to “re-enter Asia” (2012, pg. 119) after the war, forcing Japan to continuously look to Western nations and Southeast Asia for a sense of community. Despite having genuinely learned the “lesson of its extreme behaviour” (Rozman, 2012, pg. 128), Japan still lives in the shadow of the war in regards to its relations with South Korea and China. According to Welch, constant “demonization” (2014, pg. 3) from South Korea and “territorial predation” (2014, pg. 3) from China have created a mutual level of distrust between Japan and its neighbours. In an effort to redefine itself, Abe has sought to create a community based on democratic nations, with Japan identifying itself as a “mature maritime democracy.” (2012) When Abe spoke at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in 2013, he expanded upon Japan’s identity as a maritime power by adding that Japan is “Asia’s most experienced and the biggest leader of democracy.” This new identity allows Japan to work closely with the United States—its guarantor of security—and other democratic nations such as India and Australia.

Japan has shown resilience in rebranding its identity as domestic and international events dictate. The current generation of leaders has for the time being given up on joining the East Asian community, but as events unfold over the following decades, Japan may once again be forced to reconsider whether it can or should rejoin its East Asian neighbours.